|

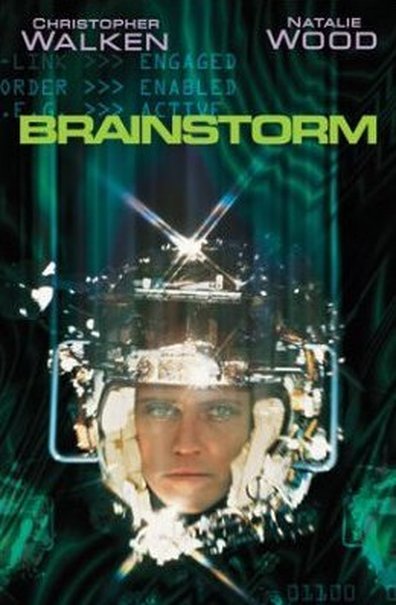

BRAINSTORM (1983)

IMDb My screenwriting career began with an extraordinary effort. I would come home from my day job as the Film Curator at the Whitney Museum in New York and write every night. I told myself I would write one scene every night and not go to bed until it was finished. Sometimes it took me half an hour. Sometimes it took the whole night. I was lucky to have a wife who was willing to support this effort. Blanche took care of our son Joshua while I was working. At the end of three months I had written 120 pages. I had a full script. That turned out to be the very first script of mine to get produced. It was called Brainstorm. It took years and years to get made, but it never would have happened without that initial three-month extraordinary effort. The original idea for Brainstorm, then called The George Dunlap Tape, was a multi-part question: What if you could live in someone else’s experiential space—if you could know their memories, share their thoughts and feelings, and live in their head? If you could do that, then who would you be? If all these things are transferrable, then what is the thing that’s doing the living? That’s the question I came up with, and I think it’s still vaguely in the finished film. Two things made the film successful for me. One was the scene where Natalie Wood puts on the helmet and sees how much her estranged husband loves her. Their marriage was falling apart because he wasn’t able to express his love properly. He wasn’t able to connect. He was too obsessed with what he was doing at work. She had every reason to want to leave him. Then he said, “Here. I made this for you.” He gave her a tape of all his memories of their time together, so that she could see into his heart. And that saved their marriage. It’s a beautiful idea that I really loved. And the music for the scene, written by James Horner, added so much emotion. That score elevated the entire movie. The other element that made the film successful for me was Louise Fletcher’s performance. She was truly remarkable and won a People’s Choice Award for her performance. I think she deserved an Oscar. Unfortunately, Brainstorm didn’t make any money. I learned very quickly that a movie that doesn’t make money is like a baby that died. You don’t talk about it. Hollywood saw it as a failure, so it didn’t advance my career at all. I had come all this way—I had gotten a movie made, and there was a huge billboard for it on Sunset Boulevard—but it didn’t change anything. I thought that if you had a movie made, you had a career. That’s not how it works. Brainstorm was supposed to start my career. Instead, it effectively ended it. CINEFANTASTIQUE magazine (March 1986)

"I could do an entire sequel to Brainstorm just from the script material that wasn’t used, but of course, it’s unlikely I’ll ever get that chance. There is a major flaw in our copyright system, that fertile ideas can be bought and sold and left to decompose in studio vaults." Cinefantastique magazine, March 1986 “Rubin’s original script opens with a nebulous image which gradually reveals itself to be cells developing into an embryo, while a caption below reads THE GEORGE DUNLAP TAPE. The embryo forms into a fetus, rapidly growing to term and about to emerge from the womb. Just as birth begins, the camera zooms into the image and we see the life of George Dunlap, rushing by at an accelerated pace. Suddenly, we are in a laboratory and into the story as it is presented in BRAINSTORM. The Dunlap character was renamed Michael Brace, played by Christopher Walken in the film. Dunlap dies at the end of Rubin’s script. The camera pulls back to reveal that the screen is really a video monitor. As the life of George Dunlap ends, a caption flashes ‘End of tape. Rewind.’ The entire movie of Dunlap’s life has been a replay of a tape. The camera dollies back further and thousands of tapes are visible on thousands of monitors. They are all ‘life tapes’ that were made and stored millions of years before, thanks to the invention of the Dunlap machine. There are no physical beings left, only lives recorded on full sensory tapes.” CINEFANTASTIQUE magazine (January 1984) Charlotte Wolter & Kyle Counts |