|

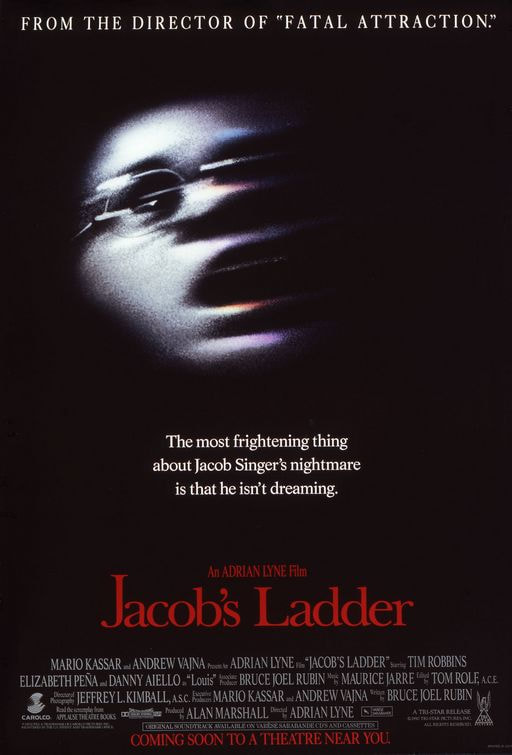

JACOB’S LADDER (1990)

IMDb READ/DOWNLOAD Bruce's first draft (1981) of Jacob's Ladder on the SCRIPTS page. The script idea for Jacob’s Ladder began as a dream: A subway late at night; I am traveling through the bowels of New York City. There are very few people on the train. A terrible loneliness grips me. The train pulls into the station and I get off. The platform is deserted. I walk to the nearest exit, and discover the gate is locked. A feeling of terrible despair begins to pulse through me as I hike to the other end of the platform. To my horror, that exit is chained, too. I am totally trapped and overwhelmed by a sense of doom. I know with perfect certainty that I will never see daylight again. My only hope is to jump onto the tracks and enter the tunnel, the darkness. The only direction from there is down. I know the next stop on my journey is hell. Partly that came out of my own fear and despair, because nothing in my life seemed to be working. In Illinois, I felt like my story had evaporated completely. My story was, “You don’t have a story.” Here you are, living in a cornfield. No friends. No work. Your wife is supporting the family. Basically, in my mind, the story was over. I could have given up my filmmaking goals and settled into a different kind of lifestyle… My story would have been: “Okay, you tried.” Instead, I woke up from my subway dream and said, “That’s a great opening for a movie.” I then tried to write my way out of hell... Jacob’s Ladder was the first movie I wrote that was delivered. By “delivered,” I mean I had nothing to do with it. I sat at the typewriter and took dictation. I typed as fast as I could, because it was just coming through. I didn’t understand where it was coming from, or why, but it was pouring through me and scaring the hell out of me as I wrote it. I remember one afternoon Blanche came into the room and stood behind me while I was writing. She was horrified. She said, “What are you writing that for?” I said, “I don’t know.” But I couldn’t stop. About halfway through the script, I got stuck. I remember pacing the room with enormous frustration because I didn’t know where I was going. I was writing a movie about a man who had died and was stuck in the bardo state, and I didn’t see a way out of the darkness. As a storyteller, I only wanted to put stories out into the world that could uplift or ennoble people—that clarify our struggle, or support us through it. When a journey through darkness ends in darkness, I often don’t want to forgive the artist. I say, “Why did they do that to me? What was the purpose of that?” Maybe it made the artist a lot of money. But I didn’t want to live by creating sadness and misery and fear. I didn’t want that in my life. One afternoon it hit me that I was writing a spiritual version of An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge, which is the Civil War story of a man who has just escaped the hangman’s noose and, against all odds, makes his way home. He sees his wife sitting on the porch. They run toward one another. Just as they are about to kiss, he feels a terrible tug pulling him backwards. The noose tightens and he dies. The entire journey home took place in a tenth of a second in his head. I suddenly realized that I was telling a feature-length version of that story. When Ghost and Jacob’s Ladder came out, I did so many interviews, and everyone would always ask me the same thing: “Why do you keep writing movies about death?” I responded, “Because it’s only through embracing death that you get to know life.” When you understand that death can come at any moment, then you see life for what it really is—totally, remarkably, unendingly precious. In a December 1983 article, One in a Million, in AFI's American Film magazine, author Steve Rebello listed ten of the best unproduced scripts in Hollywood, scripts he said “were just too good to get produced.” Rebello had read 125 scripts recommended by respected industry connections. The final ten screenplays included Jacob’s Ladder, The Princess Bride, Total Recall and At Close Range. Rebello wrote in part: Admirers of Bruce Joel Rubin’s 'Jacob’s Ladder' flat out refuse to describe this screenplay. Their only entreaty? ‘Read it. It’s extraordinary.’ And it is… page for page, it is one of the very few screenplays I’ve read with the power to consistently raise hackles in broad daylight. NOTE: Steve Rebello would have read the first draft script available to read/download above. Commenting on Rebello's article, Bruce has said: I was living in DeKalb Illinois a million miles from Hollywood and any hope of ever actually becoming a presence there when I was told about an article by Steve Rebello in American Film. In it he mentioned my script for JACOB’S LADDER as one of the top ten best unproduced scripts in Hollywood. It came out of the blue and changed my life. I had no idea it was in the works. Suddenly I was recognized and acknowledged for my work. It really was the ignition for my career. |